WHEN Henryk Sienkiewicz mingles in 1877 amid shouting crowds at the Sand Lot, the Polish writer has no way of knowing that thousands of lost bones are secreted below his boots.

Standing on the same spot a century and a half later, today’s visitors also know nothing about Yerba Buena Cemetery. The onetime municipal graveyard now lies beneath the marble-and-granite buildings of the showplace Civic Center. Government workers and tour guides have no inkling that the Main Library and neighboring Asian Art Museum stand forth in oblivious grandeur above a former necropolis. Its graves are empty. Mostly.

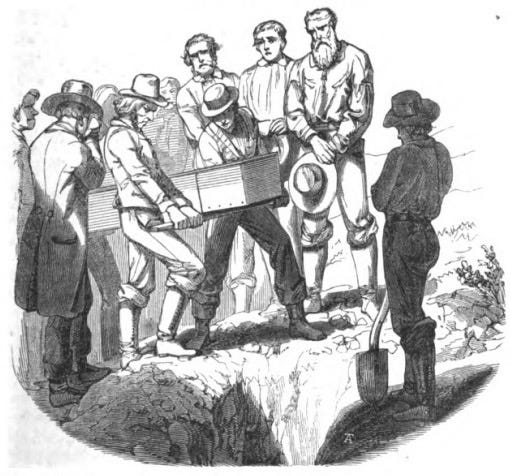

To make way for a new City Hall in the 1860s, workers flatten the bramble-covered sandhills at Larkin and Market streets, then the young city’s western edge. Municipal gravediggers disinter thousands of coffins and shrouds. Most of their contents are relocated – or dumped – out near Land’s End. But many an overlooked cadaver is left undisturbed beneath the Sand Lot, Frisco’s leading venue in 1877 for torchlight rallies and protests.

“In those days there was a long stretch of vacant sand hills between the improved part of Market Street and Valencia, which was traversed by a railroad,” editor J.F. Linthicum writes many years later in the former San Franciscan’s upstate newspaper, the Red Bluff News. “The hill and cemetery was in plain view from the steam cars. Now the hills have been removed to fill the low places, Market street has been built up and nothing remains to remind one of old times.”

The leveling produced sand to fill dimples and billabongs along the horsecar tracks on upper Market Street.

Also evicted from Yerba Buena Cemetery are bones displaced from the Powell Street Cemetery (at Lombard Street) and perhaps twenty other graveyards planted willy-nilly after the Gold Rush. They mingle with the mortal remains of goldless Forty-Niners, bankrupt Californios, Chinese workers, suicidal gamblers, syphilitic wastrels, Chilean fortune hunters, French prostitutes, unlucky sailors, native Ohlones, and thousands of other men, women, and children in a Dead Rush never mentioned by considerate history teachers.

"Many bones were found while the ground was being broken for the site of the new City Hall,” according to a 1898 report in the San Francisco Call (dug up and quoted by Brittany Hopkins in Hoodline, October 31, 2015). “Now its massive foundations stand as tombstones over the bits of skeletons …” (The new City Hall is shattered and incinerated in the 1906 earthquake and fire.)

Stacked in wagons, the remains are hauled five miles west to the new Golden Gate Cemetery, a 150-acre medley of burial grounds in the then-uninhabited sandhills of the city’s foggy northwest corner. Reburied are about 11,000 bodies from Yerba Buena Cemetery. Only 267 are identifiable. The official count, dubious because of its very specificality, lists 6,454 paupers, 4,070 Chinese, and 980 bodies buried by fraternal and social associations.

The unremembered dead are laid to rest without markers in a potter’s field known as City Cemetery, an enclave within Golden Gate Cemetery. Surrounding graveyards are maintained by lodges, Civil War vets, Colored Masons, and benevolent societies organized for French, Italian, Russian, Scottish, Jewish, Greek, German, Slavonic, and Chinese burials.

Golden Gate Cemetery will last but a half century. In 1909, real estate promoters persuade the Board of Supervisors to exhume all mortal remains from all cemeteries in San Francisco and replant them south of the San Mateo County border in tiny Colma. What with protests and litigation from private cemeteries, forty years go by before the last of the gravesites can be sold for housesites, mostly in the city’s Richmond District.

Exceptions to the cemetery ban include the historic burial plots at Mission Dolores, the San Francisco National Cemetery (military) at the Presidio, the San Francisco Columbarium (near Laurel Village), and church burials that include a monument on Franklin street for the Unitarian abolitionist, Rev. Thomas Starr King.

Exhumed from City Cemetery and reburied at Skylawn Cemetery in Colma are about 11,000 former residents, mostly paupers; from the associations and benevolent societies, about 7,000. Unknown is how many bones are missed by the excavators. (Thousands of unclaimed marble tombstones become filler in seawalls; some are stolen by respectable grave robbers in need of flagstones, the inscriptions facing down.)

In the early years of the twentieth century, City Cemetery is risen from the dead as Lincoln Park (dedicated in 1915 as western terminus of the ballyhooed transcontinental Lincoln Highway, old U.S. 30). It becomes the site of a municipal golf course and a major museum of fine arts, the Palace of the Legion of Honor.

Archaeological investigators conclude in 1993 that about 700 of the dear departed still lie beneath the floor of the Legion of Honor’s elegant courtyard. At its entrance is The Thinker, one of several castings of August Rodin’s bronze sculpture. The original version is the centerpiece in Paris for his sculptural group, La Porte de l’Enfer (The Gate of Hell). The Thinker stares ever downward through the pink granite paving blocks. If he were not a hollow 1,200-pound casting of bronze alloys, he might be contemplating hidden stiffs at the gate of Hell.

Back at the former Sand Lot, excavations in 2001 for the new Main Library unearth ninety-seven skeletons and bodies from Yerba Buena Cemetery. The bones, unclaimed and anonymous, are reburied in Colma.

"Some of the remains uncovered had been undisturbed for 150 years,” reports Sam Whiting in the San Francisco Chronicle (May 13, 2001). “The coffins have been reduced to just pieces of wood and a few nails, but the skeletons are remarkably preserved. The other day one was uncovered with three molars showing in his skull and a wooden button on his midsection. He was estimated to have died at 19.”

Nobody knows how many others are enriching the soil below the Main Library and the Asian Art Museum, site of the forgotten Sand Lot where Henryk Sienkiewicz once watched a crowd explode with anti-Chinese bigotry.

Five generations later, no ghost sightings have been proven – so far as we know – in the unacknowledged mausoleum known as the Main Library.

That was super interesting and Mr. Ludlow’s way with words is …I don’t even know the adjective. But “dimples and billabongs” “respectable grave robbers”. I loved the whole thing!! So enjoyable.